Form your team right

Summary

If you don’t form your teams right, you won’t set them up for success. People matter most in software development and otherwise. A players drive a high performing team culture.

Avoid the Temba Bavuma effect, where you nominate a leader without understanding if they can be a role model for their colleagues. Instead, staff the team with the best people you can find, and then choose a leader amongst them.

Beware of the Zootopia effect, where you take notions of the growth-mindset and cultivation too far. There’s a limit to how many novices and advanced beginners a team can support.

When forming teams, spend some time listing the problem you’re solving, the skills you need and the roles that have these skills. Write a job description if necessary. This’ll help you be clear about the kind of team you’re trying to form.

Over the last several months, I’ve written about how to help teams work better, using asynchronous collaboration techniques. One of my underlying assumptions is that these teams include the best possible people in them. And that’s only fair, since in software development, people matter most.

“The most important part of getting cost-effective software development is to hire the best team you can, even if the individual cost of the developers is much higher than the average. A few high-ability (and expensive) people will be much more productive than many low-ability (cheap) developers. That productivity difference means that a few high-ability people will produce software more cheaply even if they cost more on a daily rate.”

If your business needs you to stand up such teams regularly, you may get good at creating a team of A-players for every software project you handle. But often, this diligence evaporates when you have to form a team for an uncommon purpose. It seems obvious to say that poorly formed teams are woefully ineffective, but I see it so often that I’d be remiss not to state the problem. So in today’s post, I want to call out two common problems I see leaders repeat when forming new teams. And what good is it to state a problem without potential solutions? I’ll get to those by the end of the article.

The Temba Bavuma effect

The first problem has its explanation in cricket. Sorry, I can’t help it. I’m Indian and I grok cricket metaphors. Temba Bavuma is the captain of South Africa’s test and ODI cricket teams. He’s a pretty handy ODI batter, and in an era that’s been relatively tough for test batting, he’s not too bad in tests either. In fact, he scored a century in a recent test. Temba, however, isn’t a T20 player. For the uninitiated - T20 is a fast-paced version of the same sport.

For their 2022 World Cup campaign, South Africa made the mistake of naming Bavuma as their captain. Unlike ODIs and test cricket, Bavuma is a liability in T20s. By giving him the captaincy, South Africa blocked off one crucial spot on their team. It also doesn’t help when the captain doesn’t fire. After all, if you can’t contribute to the team, can you hold others accountable for their performances? Unsurprisingly, South Africa failed to make it to the knockout stage of the tournament. I won’t blame it all on Temba, but the example just goes to show that on a team playing a pressure-packed sport, you can’t have a non-performing captain. The phenomenon of a non-performing captain is what I call, “The Temba Bavuma effect”.

Teams at work aren’t different from sporting teams. At work, teams are usually smaller than the 11 that take the field in cricket. And while the pressure may not be as intense as a three-hour game of T20 cricket, we can all agree that work is rarely just a walk in the park. Picking a leader before you pick your team is a cardinal error. Unless you’re certain that you’ll pick someone for a team, regardless of whether they’ll be a good leader, leave the leadership decision to later. Pick the best team possible. Figure out if they even need a nominated leader. And if they do, pick someone to be a “first amongst equals”. They’ll have the respect of their team because of their skills and contributions, and their place will not be in question.

The Zootopia effect

The name of the second problem has a rather cute origin. In the endearing Disney movie, Zootopia, there’s a popular refrain - anyone can be anything. I’m a firm believer in that maxim. In fact, I’ve made my children repeat that line dozens of times. In principle, it also aligns with Carol Dweck’s idea of a growth mindset. Many employers, including my own, extend this thinking to a cultivation culture - where the organisation or team succeeds by growing people.

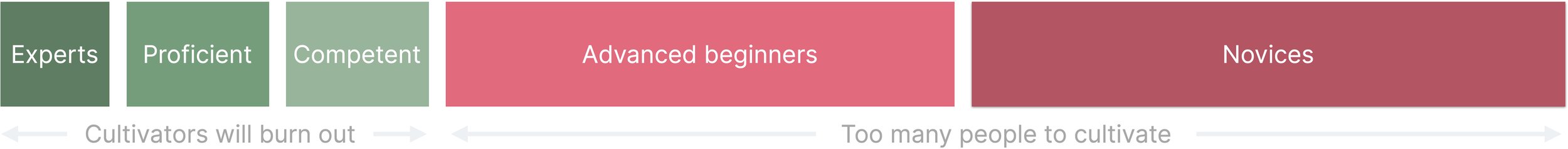

When you have too many people to cultivate, the cultivators burn out

And there lies a tiny trap. Of course, anyone can be anything (if they put their mind to it) and you must support a cultivation culture. But there are limits to this mindset. If only a minority of your team are expert, competent or proficient and the rest are novices or advanced beginners, you’ll burn out the former while supporting the latter. These are teams where everyone’s miserable. People with higher proficiency feel like they’re always stretching themselves. The learners are also under pressure to deliver and to learn faster than they may consider reasonable. This is “The Zootopia effect”.

A balanced team, where cultivation doesn’t come in the way of delivering

If you’re standing up a new team, it’s tempting to leverage it with just a few people who’re expert, competent or proficient. It feels like getting the most bang for your buck. It rarely yields the highest-performing teams, though. Instead, take a 10-70-20 approach to build teams.

10% of your team can be at the expert level.

About 70% must be at the proficient or competent levels.

The remaining 20% can be at the novice or advanced beginner levels.

Having a smaller percentage of novices and advanced beginners doesn’t mean that you’re discarding the growth mindset. After all, the experts can help everyone else grow. People at the proficient or competent levels can learn from the experts and each other as well. Composing the team this way ensures that you don’t lose sight of results while aiming for cultivation.

To form the right team, start with the basics

Forming teams needn’t be rocket science, but it will take some thinking. This is where a few hours of deep, asynchronous work come in handy. I enjoy thinking through a few questions when trying to construct teams.

What problem are we trying to solve?

What skills do we need to solve this problem?

Which roles map to the skills we need?

At what level of proficiency must we perform these skills?

What’s the smallest capacity that the team can get away with, at the start?

Once you’ve answered these questions, you’ll have a rough idea of the people you need and how many of them you must start with. This is an excellent time to turn to an age-old tool—the venerable job description. Job descriptions are handy for a few reasons.

They help you get explicit about what you expect from a team member.

If you need to hire externally, or internally, they’re a consistent artefact you can circulate amongst candidates.

A good job description can be quite light. I usually add the following sections to any job description I write.

Context of the team we’re hiring for.

A blurb about the role and who it reports to.

Responsibilities and day-to-day tasks.

Necessary background, skills, attributes and experience.

Operational information, such as location and who makes the hiring decision.

Once you’ve written up these role descriptions, you can hold yourself accountable to build your team with the best people available. When you find yourself the best people, pick the most natural leader amongst them to avoid the Temba Bavuma effect. It’s ok if a minority is still learning the ropes. As long as you have enough people to support them, you’ll avoid the Zootopia effect.

I find you can preempt many problems for a team if you were to set the team right. To give yourself the best chance of winning a game, you need the best possible team on the park. Of course, there’s Murphy’s law and all that. Then again, a strong team is always better at handling unforeseen teams as compared to teams that are burning out or carrying B-players.

Creating a team of A-players has a positive impact on a culture of excellence as well. Such people don’t just raise the performance levels on your team, they also help you attract other people like them. And if you care about cultivation, these are the people who can help grow others as well. Isn’t that something we can all get behind?