Why you may find it tough to introduce asynchronous work in your team

In the last article, we discussed why it may be a challenge for you to introduce asynchronous work in your organisation. Organisational culture and inertia are bottlenecks for adopting any long-term change. However, the first port of call for any change journey is your immediate team. If your colleagues don’t commit to change, it’s unlikely that even in a conducive organisational culture, a shift will happen.

As an evangelist, coach, consultant and change maker, anticipating push back from your team will help you deal with it as well. So in this article, I’d like to share with you some blockers you’re likely to encounter from your colleagues. Let’s get started.

Disbelieving is hard work

In his excellent book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman describes the notion of theory induced blindness.

“Once you have accepted a theory and used it as a tool in your thinking, it is extraordinarily difficult to notice its flaws.”

Before I go any further, I have to admit that I’m as susceptible to this blindness as anyone else. And I urge you to examine my theories with a fine-toothed comb as well. All I ask is that you don’t give a free pass to other theories just because they’ve been around for a while. With that said, let’s come back to something we discussed in the previous article - the venerable agile manifesto.

In the two decades of its existence, the agile movement has been a revolution in software development. It’s hard to argue with its fundamental premise.

| We are uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it. Through this work we have come to value: | ||

|---|---|---|

| Individuals and interactions | over | processes and tools |

| Working software | over | comprehensive documentation |

| Customer collaboration | over | contract negotiation |

| Responding to change | over | following a plan |

| That is, while there is value in the items on the right, we value the items on the left more. | ||

The trouble is with how some of us have misinterpreted the manifesto. Remember that asynchronous work needs some discipline around processes and tools. As I mentioned earlier, there’s no black magic with asynchronous work - written communication is at the heart of it. Teams, however, sometimes think that processes, tools and documentation run counter to the philosophy of agile. This is a gross misinterpretation. Pay special attention to that last line - there is value in items on the right. The authors just valued items on the left more. Let’s take the example of documentation. My colleague and author of the agile manifesto, Martin Fowler, said this way back in 2005.

Almost immediately I feel the need to rebut a common misunderstanding. Such a principle is not saying that code is the only documentation. Although I've often heard this said of Extreme Programming - I've never heard the leaders of the Extreme Programming movement say this. Usually there is a need for further documentation to act as a supplement to the code.

How about processes and tools? Martin has a point of view about that as well in his 2006 essay about offshore development.

“Agile methods downplay documentation from the observation that a large part of documentation effort is wasted. Documentation, however, becomes more important with offshore development since face-to-face communication is reduced… As well as documents, you also have more need for more active collaboration tools: wikis, issue tracking tools and the like.”

More recently, in 2015, well before the remote work revolution Martin wrote rather astutely about an oft-misunderstood principle of the manifesto, “The most efficient and effective method of conveying information to and within a development team is face-to-face conversation.” Martin urges us to reconsider how we build high performing remote teams.

“But all of this is just making the point that a given team usually collaborates better when co-located. It doesn't make any argument about getting a better team by supporting a remote working pattern. The first value of the agile manifesto is ‘Individuals and Interactions over Process and Tools’, which we should read as encouraging us to prioritise getting the best people we can on the team and helping them work well together.”

The world has changed considerably since that 2015 article by Martin, more so since the start of the global pandemic and even more so since we’ve had the agile manifesto. Yet, there’s a chance that people cling to a gross misinterpretation of the manifesto and are more loyal to it than the authors themselves. When people close themselves out to flaws in these theories they’ve created for themselves, despite evidence to the contrary - you’re likely to face theory induced blindness, as Kahneman described it.

Loss aversion

Two of the primary observations of behavioural economics are “loss aversion” and the “endowment effect”. Simply put, here’s how you can describe each of those behaviours.

Loss aversion: the tendency to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains.

Endowment effect: people are more likely to keep something they own than acquire something they don’t already own. This relates closely to status quo bias - our tendency to maintain our current state of affairs.

Nobel laureate Richard Thaler explains the above graph through the following two choices. The numbers in the last column represent the percentage of subjects that chose each option.

| Problem 1. Assume yourself richer by $300 than you are today. You have the following choices. | ||

|---|---|---|

| A | A sure gain of $100, or | 72% |

| B | A 50% chance to gain $200 and a 50% chance to gain $0. | 28% |

| Problem 2. Assume yourself richer by $500 than you are today. You have the following choices. | ||

|---|---|---|

| A | A sure loss of $100, or | 36% |

| B | A 50% chance to lose $0 and a 50% chance to lose $200. | 64% |

These results are quite fascinating. In problem 1, we act risk averse - we want to keep the sure gain of $100. In problem 2, where all choices are bad, we’re risk seeking. This observation has implications on driving any kind of change with our teams as well.

We’re likely to overvalue what we have - in this case, an existing way of working; however flawed. Adopting a new way of working is risky, and when we are already "endowed" with something, we're less likely to seek that risk. Staying with the status quo is easier.

We’re likely to be most open to change when things are terrible. For example, when people burn out, or when stakeholders are unhappy, or when our colleagues are quitting the team. Yet in their minds, most rational people don’t want to get to this point.

The challenge for you as the change-agent, is to convince people to experiment with change; while helping them deal with their own tendency to be loss-averse.

Change is not a straight line

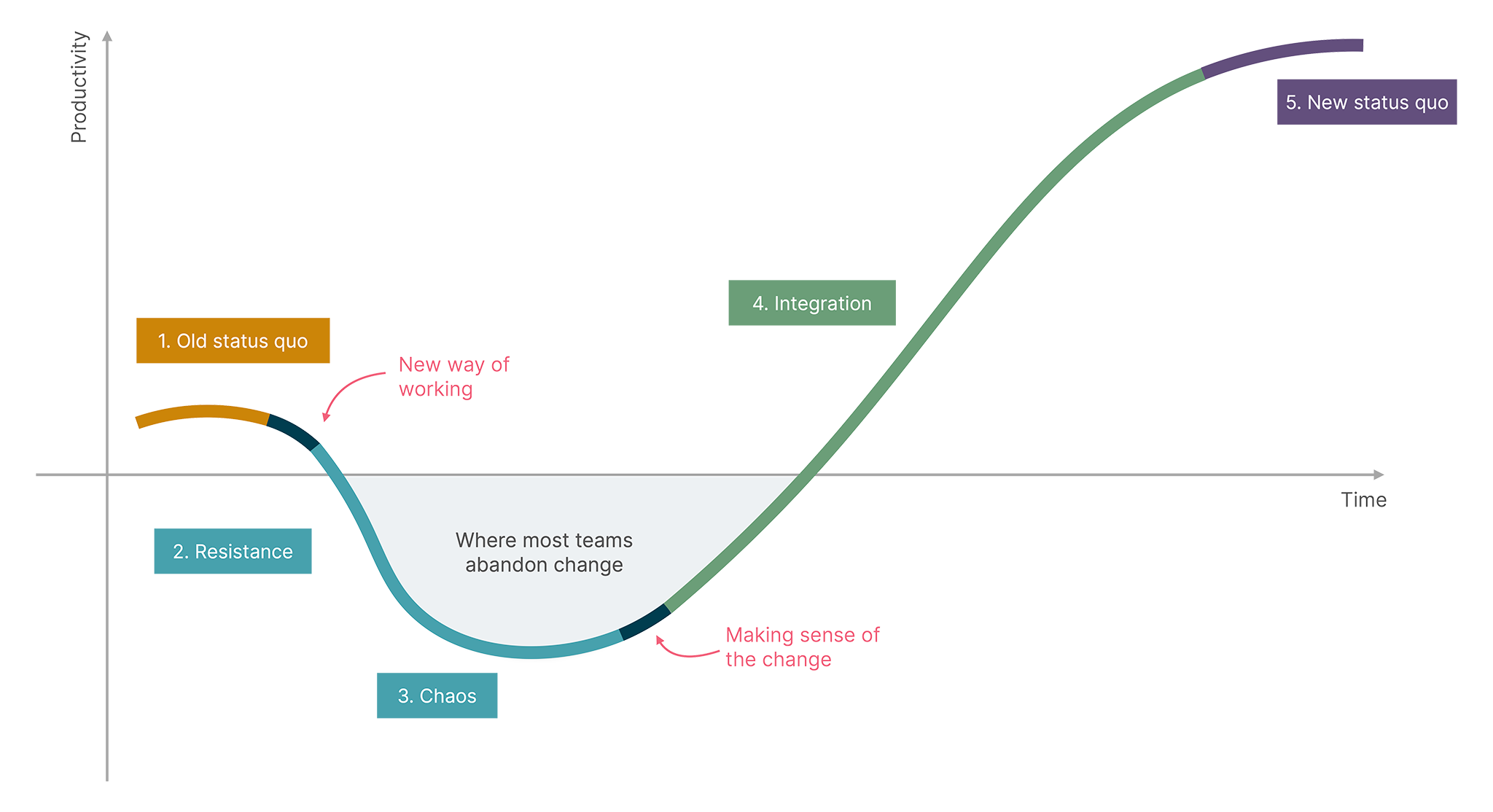

Virginia Satir’s process of change

Our hope for change is that the progress should be linear - as close to a straight line as possible. Reality, however, is quite different as Virginia Satir postulated in her now famous “Process of change model”. While the full details of the model are beyond this article, the above diagrammatic adaptation should help you expect what the change journey will look like - from the old status quo; to the new status quo.

Whenever we introduce a foreign element - in this case a new way of working for a group of people comfortable with their current way of working, there’ll be inevitable resistance. There’s a high probability that this resistance will lead to a period of chaos where productivity dips below a threshold. This is usually where most teams and organisations abandon the change and deem the intervention as a failure. Successful transformations stay the course through this period of chaos, until the team in question can make sense of the change, integrate it into their work and eventually settle at a much higher level of productivity than where they started.

Whether it is through leadership support or skillful coaching or with the help of like-minded evangelists on the team, your goal should be to make the period of chaos as short as possible.

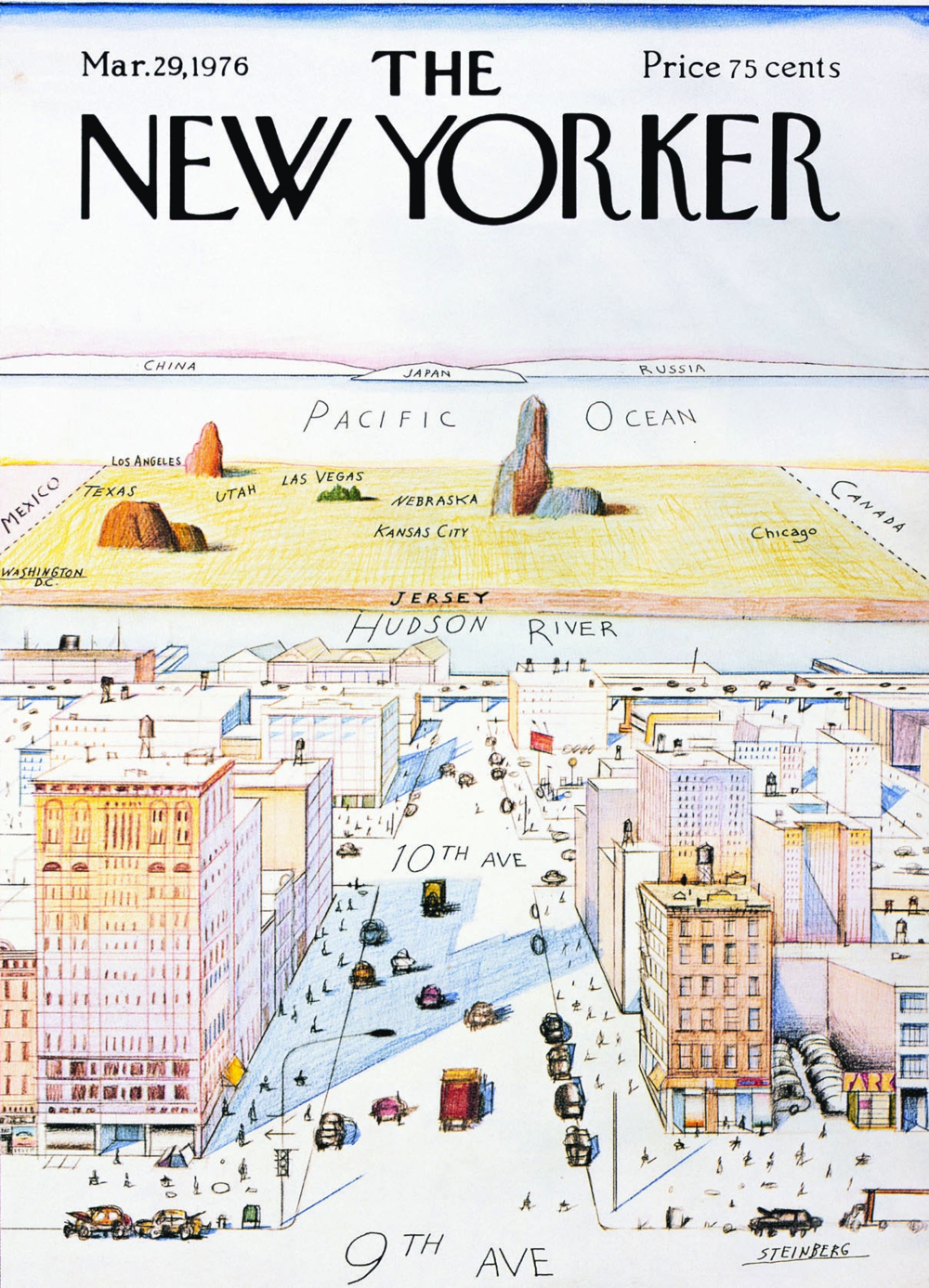

View of the world from 9th Avenue

On March 29, 1976, the New Yorker magazine released a delightful cover - “View of the World from 9th Avenue”. While the image intends to present Manhattan’s view of being at the center of the world; it’s also a great metaphor for the way our brains work. If you look closely at the image, you’ll notice that the bottom half covers just two blocks - 9th to 11th avenue. The next quarter of the image not just includes the rest of the United States, but you also see China, Japan and Russia looking rather equidistant from the viewer’s perspective.

In a similar way, our ability to forecast the future is quite poor. We can tell each other with some detail, what may happen today, this week, in the next fortnight, maybe even the next month. Ask us to plan for something that’s a year down the line, and we struggle. This relates to our earlier point about the endowment effect. If your current way of working is inconvenient, but is doing the job; you’re less likely to foresee problems like burnout, escalations and resignations a year down the line. You’re more likely to respond to those risks when they actually become real. As a change maker, you’re trying to mitigate future risks. People’s tendency to discount the future can come in the way of that.

Until this point, we’ve discussed all the reasons your efforts to introduce a modern way of working could fail. While this can be demoralising to read, my intention is to prepare you for what you should expect. If you’re lucky to not face these challenges - brilliant! Ok, let’s do a recap.

There’s an oversimplified model of agile that many people hold in their minds. This model pushes back against processes, tools and documentation; which are at the centre of asynchronous agile development.

People have a tendency to be loss-averse. Giving up an existing way of working induces a feeling of loss. People are more open to change when shit has hit the proverbial fan, but you probably want to make changes before you get to that point.

Most changes in ways of working are likely to lead to a period of resistance and chaos when the team’s productivity dips. This is when teams often abandon the change. The challenge is to stay the course and integrate the new ideas into a higher productivity status quo.

Most of us can’t foresee anything beyond the immediate future. So even if our current ways of working create problems somewhere down the road; we’re likely to discount the future and focus only on the here and now.

As I draw this article to a close, I urge you to think about why you want to improve your team’s ways of working to include more asynchronous practices. To me, the benefits are obvious.

Better work life balance.

An enhanced ability to include people from different:

locations;

backgrounds & personal situations;

& personality types.

Improved onboarding and knowledge sharing.

Communication practices that support scale.

Getting time back in our lives for deep work.

A culture that defaults to action.

What’s in it for you and your team?